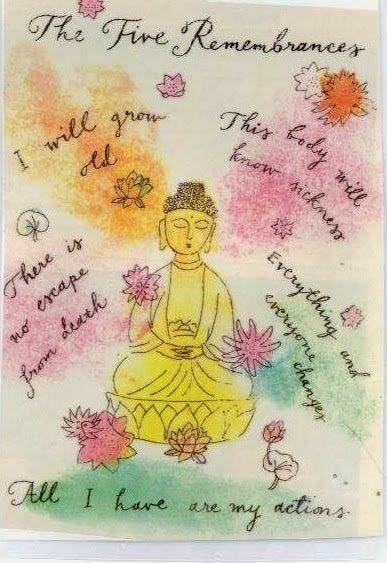

Five Remembrances

Think See-Judge-Act

We are starting the Buddhism section in my class...

There are Five Remembrances of Buddhism. Using the see-judge-act method, how do these five remembrances fit into our lives, and what can we do to bring about the Kingdom of God here and now?

The five are:

• I am of the nature to grow old. There is no way to escape growing old.

• I am of the nature to have ill health. There is no way to escape having ill health.

• I am of the nature to die. There is no way to escape death.

• All that is dear to me and everyone I love is of the nature to change. There is no way to escape being separated from them.

• My actions are my only true belongings. I cannot escape the consequences of my actions. My actions are the ground upon which I stand.

I use these in my comparative religion class; I remind the class that they are intended to be recited. They’re designed to be memorized by all practicing Buddhists. If we look hard, many of Thomas Merton’s writings reflect those five. Thomas Merton, a prominent Christian mystic and writer, was deeply influenced by Buddhist teachings, and his writings often resonate with the principles of impermanence and karma. (I weave Merton into everything I teach, Lol)

I tell them these first three, of course, drove the Buddha to become the Buddha. These were the central wake-up calls of his life before he “woke up”: sickness, old age, and death. It’s so commonsensical.

We experience sickness, old age, death, and these final two. “All that is dear to me and everyone I love is subject to change.”

This represents impermanence. “There is no way to escape being separated from" ~ and here we touch on the essence of dukkha, or unsatisfactoriness. Dukkha is a fundamental concept in Buddhism, referring to the unsatisfactory nature of life due to the impermanence and change. Everything will change; nothing will ever be as I desire it, as I need it to be, or as I believe it should be. I can’t hold onto the perfect thing. I can’t hold onto anything.

Do we see where Joseph Cardijn understood this concept also? Think of the time of imprisonment and the cause/effect.

Think of Pacem in Terris. #47. "But it must not be imagined that authority knows no bounds. Since its starting point is the permission to govern in accordance with right reason, there is no escaping the conclusion that it derives its binding force from the moral order, which in turn has God as its origin and end."

Remembrance #5 might be the most interesting. “My actions are my only true belongings. I cannot escape the consequences of my actions. My actions are the ground upon which I stand.” This reflects karma. I tell them….I’ve heard it said, and maybe you have, too, that we own our actions “but not the fruits of our actions.” We experience the consequences, but we don’t receive the rewards.

Within our Christian tradition, maybe we see what Merton saw in Zen; we can understand this to a certain degree as practice–verification, the central teaching that the meaning of what we do is expressed, complete, in what we do. What we do is the essence.

I encourage my students to make the Five Remembrances a daily routine. Whether they print them out on a 5×7 card, write them down and stick them next to their mirror, or tape them on their kitchen counter or refrigerator door, the goal is to let these five truths soak into their skin. You’ve always known them because they’ve always been true. It's about actively engaging with these teachings, not just passively understanding them.

But it is best to remind ourselves anyway. We forget. We let ourselves think otherwise. We should remember every day, just like Merton and Cardijn did: What we do is the essence.

(The Five Remembrances in Buddhism, offered by Thich Nhat Hanh in The Plum)