Introduction

I recall learning about the corporal and spiritual works of mercy in RE, probably in secondary school. And as I think about the manifestations of these works in the world around me, I am taken back to a letter written by Cardinal Joseph Cardijn (1882-1967), possibly in the 1960s.

The Cardinal was reflecting on a journey he made to England, not long after his ordination in 1906. He described that visit as possibly the best retreat he made in the early years of his priesthood. What struck me about his letter was the contrast he drew between the Catholic clergy he ate with in Salford and the Protestant dock workers and union leaders, whose faith he described as “devout.” Their lives were characterized by “faith in action.”

While it would be true to say that prayer is a form of action, Cardijn was convinced that his fellow priests, with whom he shared the evening meal, saw him as being “imprudent” when he sought to make contact with and learn from those who were dock workers. He was to learn from Ben Tillett, one of the union leaders of the Great London Dock Strike of 1889, that his “imprudent” behaviour placed him in good company: Cardinal Manning had stood in solidarity with the workers and was instrumental in gaining for them many of the improvements in their work conditions that they sought.

Cardijn spent his priestly life forming young workers as apostles of Christ. The method he taught them to use - See, Judge, Act - is a form of prayer when Christ is part of the conversation about what matters most to those who gather to discern the truth and decide how to act for the good of others.

And those who gather to reflect on the Gospel you are about to read can be assured of the power of Christ to endure all manner of suffering that comes from doing the Will of God.

The Gospel

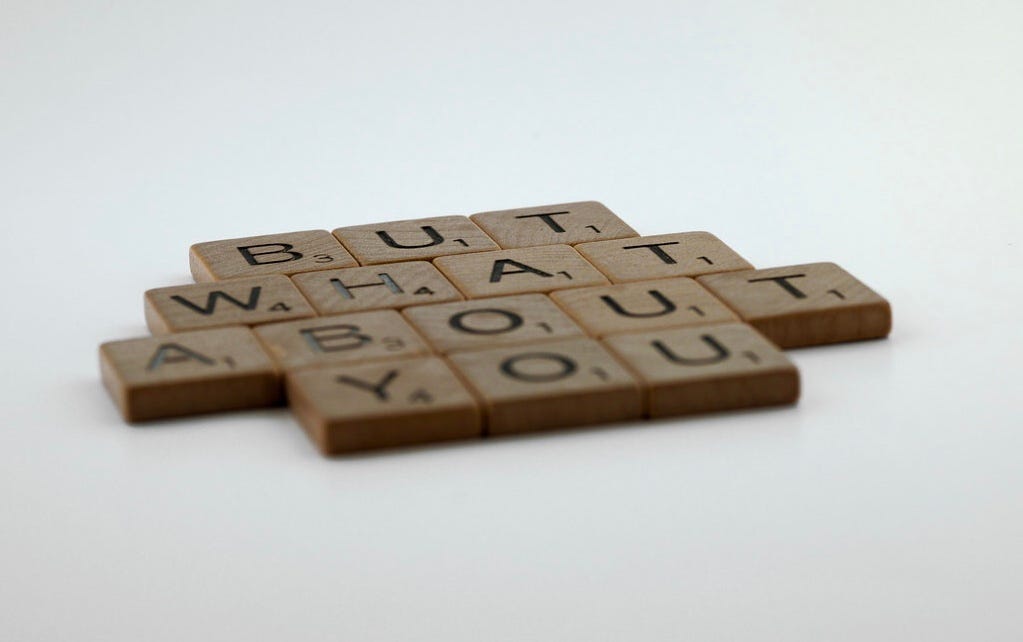

Jesus and his disciples left for the villages round Caesarea Philippi. On the way he put this question to his disciples, ‘Who do people say I am?’ And they told him. ‘John the Baptist,’ they said ‘others Elijah; others again, one of the prophets.’ ‘But you,’ he asked ‘who do you say I am?’ Peter spoke up and said to him, ‘You are the Christ.’ And he gave them strict orders not to tell anyone about him.

And he began to teach them that the Son of Man was destined to suffer grievously, to be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and to be put to death, and after three days to rise again; and he said all this quite openly. Then, taking him aside, Peter started to remonstrate with him. But, turning and seeing his disciples, he rebuked Peter and said to him, ‘Get behind me, Satan! Because the way you think is not God’s way but man’s.’ (Mark 8:27-33)

The Enquiry

See

What do you learn about Jesus from this event recorded in Mark’s Gospel? What do you learn about Peter?

Why is Jesus in conflict with the elders, the chief priests and the scribes? Why do they want him put to death?

Do you read this Gospel as a theological statement or as an historical statement?

Judge

What do you make of the interaction between Jesus and his apostles?

Ideally, how should the apostles have responded to what Jesus shared with them?

How is your faith affirmed and/or challenged by what you learn about Jesus and about the early Christian community from which we received the Gospel of Mark?

Act

Working from the insights you have gained through interacting with the Gospel, what do you want to change in the world and/or the Church?

What action can you carry out this week that will contribute to the change you would like to make?

Who can you involve in your action, when, how often and how?

Image source: Brett Jordan (Creator): ‘But you,’ he asked ‘who do you say I am?’, Flickr, CC BY 2.0